Researchers have developed a new substance to fight bacteria: special liposomes act as decoys for the body's cells, allowing the immune system to do its job. But some doctors and scientists are skeptical.

A study published in the journal "Nature Biotechnology" unveils an engineered substance, which its makers hope will present an alternative to antibiotics in the fight against bacterial infection.

Resistance to antibiotics is a serious, growing worldwide problem. The World Health Organization(WHO) in a 2014 report warned that "antibiotic resistance is no longer a prediction for the future; it is happening right now, across the world."

Although any new substance would have to undergo a lengthy process before it can be used as medicine, the Geneva-based biomedical startup Lascco has already announced clinical trials for next year. Some doctors and scientists stress that the new substance will likely not be able to replace the use of antibiotics.

'Irresistible bait'

The scientists developed artificial nanoparticles made of lipids, or "liposomes," that closely resemble the membrane of host cells. Also known as CAL02, these artificial membranes would be introduced into the body of a person with a severe bacterial infection to attract the toxins produced by the infecting bacteria.

"The toxins will preferentially bind to the liposomes instead of attacking the cells in our body, and stay trapped there," explains Annette Draeger, a co-director of the study. Since bacteria produce these toxins to repel an attack by immune cells, neutralizing such toxins would allow the body's immune system to then defend itself against the infection.

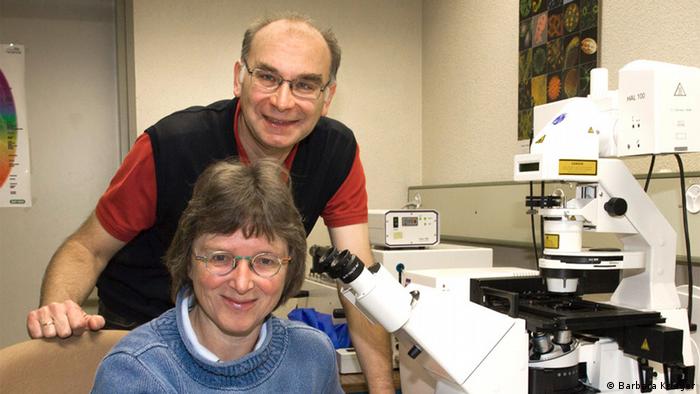

Draeger, who works at the Institute of Anatomy at the University of Bern in Switzerland, told DW the 18-member team came across the idea of developing a decoy system while studying how cells are able to repair their membranes after being attacked by bacterial toxins.

Bacterial toxins bind to certain unstable lipid regions within the cell membrane. "We have made liposomes which are an improved, more stable, replica of these regions," Draeger said.

Eduard Babiychuk, another of the study's co-directors, describes the liposomes as "irresistible bait" for bacterial toxins. "The toxins are fatally attracted to the liposomes," Babiychuk said in a statement.

Rising antibiotic resistance

Antibiotics have only been around for about a hundred years - but that represents many millions of generations in the short lifespan of a bacterial organism.

Over these time spans, bacteria have adapted to their new environments, including by developing resistance to antibiotics. Resistance is passed down through generations - and can even be exchanged among bacteria by mere contact.

The problem of antibiotic resistance is exacerbated, the WHO says, when antibiotics are dispensed in the case of viruses - against which they are ineffective - and when patients stop taking antibiotics once they start feeling better, rather than completing the full course. Overuse of antibiotics in the livestock industry is also likely increasing bacterial resistance.

Just last week, the German healthcare provider DAK released a study indicating that German doctors often prescribe antibiotics when they are not necessary, such as when the patient has a cold virus.

The WHO reported 450,000 cases of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in 2012, as well as an increase in antibiotic resistance for more common bacterial infections such as urinary tract infections, pneumonia and bacterial infections of the blood such as sepsis.

Resistance to antibiotics becomes a serious problem especially for people who are already ill or injured. Strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, spreads in hospitals with deadly consequences.

Concentrate on rare infections

The bacterium Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of death worldwide

Although the medical community would be receptive to alternatives to antibiotics, some doctors remain skeptical of liposome treatment.

Frank Martin Brunkhorst, a senior doctor and head of clinical trials at the University Hospital of Jena in Germany, told DW "I'm not sure this could definitely work."

He cites a number of studies with liposomes and phospholipids that didn't work as drugs - "All these trials failed."

Brunkhorst sees as the main problem that the liposomes do not actually kill the bacteria. Staph infections are most likely based in soft tissues, he explains, so "If you stop the liposome treatment, the toxins could come back to the bloodstream."

Brunkhorst recommends concentrating this treatment on more rare Streptococci infections, like Toxic Shock Syndrome, that suddenly introduce many toxins into the bloodstream. Because these patients "could die within hours," Brunkhorst says - too short of a time to undergo the lengthy diagnostic process and determine the best antibiotics treatment.

Hans-Georg Sahl, a pharmaceutical microbiologist at the University of Bonn in Germany, echoes this sentiment. "Such a measure could not be a complete replacement for antibiotics," Sahl told DW. But he could imagine use of liposome therapy to support antibiotics treatment, thus reducing antibiotic resistance.

Indeed, Samareh Azeredo da Silveira Lajaunias of Lascco, which is planning clinical trials for 2015, told DW "The planned clinical study will assess CAL02 as an adjunctive treatment to standard of care, including antibiotics."

No comments :

Post a Comment